I seem to drink a lot of Cabernet Franc.

Why is this? Well, part of the reason is my natural attraction to undersung varietals. And Cab Franc

is that. Part of it is because of the price. When I'm in the mood for a French red, and don't have the do re mi for a Bordeaux or Burgundy or Chateauneuf-du-Pape (which is often), I reach for a Loire red as a better value for my limited bucks. Another reason is my longstanding interest in the wines of Long Island, where Cab Franc grows well. And, finally, importer Kermit Lynch seems to love the Loire, and, as a subscriber to his wine mailings, I sometimes pop for a case of his Cab Franc offerings. Usually, I am not disappointed, though I have to admit, making your way through a case of the often astringent grape can be a challenge.

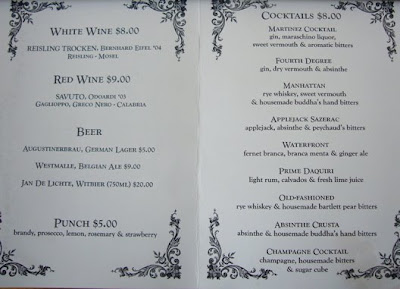

So, when I learned that the first 2009 tasting of the Wine Media Guild would be Cab Franc from all over the world, it was like Darth Vader saying to me, "Robert, it is your DES-tiny." Two good speakers were on hand, Long Island winemaker Roman Roth and restauranteur Paul Grieco, owner of Hearth and Terrior in the East Village. Roth was the epitome of European reserve and modesty. Grieco was the epitome of American bravado, even if he is from Canada.

The talented and smart Grieco a member of a brazen breed I like to call the Wine Jocks. These folks, usually men, usually young, approach their enthusiasm for wine the same way sports fanatics talk about last night's game. Every opinion that is thought is also expressed, and forcefully. Attitudes are personal. Cockiness and machismo abounds. I've seen many speakers at Wine Media Guild lunches. Grieco is the only one I'd ever seen who actually worked the room. He didn't stand where he was seated and speak from there. He paced and gestured. I think some members were a bit stunned by this behavior, but the talk was all the more effective for his animation and lung power.

From Grieco I learned a lot about Canadian wine. To you and I and the man on the street, Canadian vino means one thing basically: Ice wine. That's what we see on the shelf. Paul said there is much more to Canadian wine, and there are some great makers, but America sees little of it, because Canadians drink most of it themselves. Also, winemakers sell most of their wine to the government, which then distributes it to the public. (There are no independent liquor stores.) With a guaranteed buyer like that, there is little incentive for vintners to sell wine to the U.S., where they would make considerably less money.

There were four Canadian Cab Francs in the tasting, but, sadly, none of them were impressive. I found them all too flowery and pretty. Grieco called them "mediocre."

There were many French bottles. The thing with Loire Cab Francs, it seems to me, is there's a lot of sameness. With most Chinons, say, you'll get the cherry flavors, the dustiness, the green notes. And then you'll get them again and again, bottle after bottle. It takes great artistry for a wine to stand out. The best among the French wines, I'm happy to say, came courtesy of a WMG member, importer Frank Johnson. His Jean-Paul Mabileau Cuvee Graviers 2006 Saint-Nicolas de Bourgueil was the wine of the day in my opinion: understated, with a dignified nose and palate, and nicely balanced. Others seemed to think so to: both bottles were finished by the end of the lunch.

Johnson told me he sampled Mabileau's 2007, and, not liking what he was tasting at all, asked "How many 2006s do you have left." He bought them all.

Of the Long Island Cab Francs, my favorite was the Shinn Estates. To me, this maker rarely falls down with this varietal. Just the right amount of fruit vs. vegetal notes, and well-structured. There was a $60 job from Schneider Vineyards. I don't really think a $60 American Cab Franc has much reason for being, and, while the Schneider 2005 was rich and big and not bad, it wasn't worth three Jacksons.

The surprise of the tasting were three Canadian Cab Franc ice wines that were served at the end. Grieco said these have become a big hit in the Far East market, where ice wines are loved and red is a lucky color. The best by far was a Pillitteri Estates Winery Icewine 2006 with a fascinating, original nose of rhubarb and strawberries, and similar notes on the palate.